Terraqueous Feminisms

By Gina Heathcote

Recent events in the Red Sea underscore the intertwined nature of maritime and land military endeavours and the economic drivers of maritime encounters. It has been deeply troubling to try and make sense of a global community that embarks on military strikes to ‘save’ commercial ships from attack, while refusing to speak out and act in response to genocide. Elsewhere feminist and gender scholars engage armed conflict, often through the frame of the United Nations Security Council’s women, peace and security agenda. Maritime matters – security, economics, research, navigation, protections – and the laws that regulate maritime regions have received little feminist analysis. In my research I consider feminist understandings of the international law of the sea through a posthuman feminist lens and argue for terraqueous feminisms, that is feminisms that disrupt the land-sea distinction and which explore the co-constitutive nature of land-sea relations.

A posthuman feminist approach, informed by Braidotti and Jones, pays attention to the nonhuman and human Others; it aims at understanding, thinking with, and learning from traditions and encounters that seek to disrupt the unencumbered man of enlightenment thought. From this perspective we might ask how feminism might arrive at the ocean and the international law of sea. Three objects help underscore the ways in which the global order has already conceptualised the sea, the oceans, watery spaces on a map, as not land, as ungendered, as flat, uninhabited, neutral.

The map. The ship. The robot.

The map

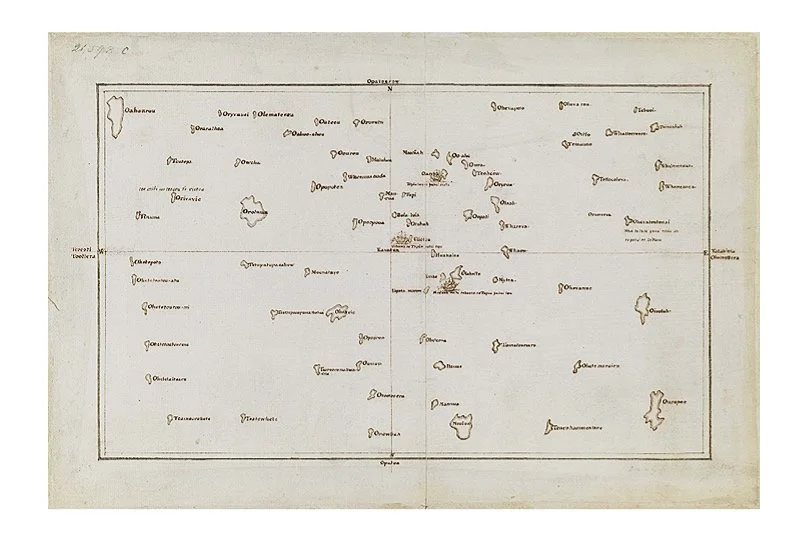

The international law of the sea, governed by the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, provides a map of sorts, marking out maritime jurisdictions, from coastlines to the High Seas. For international lawyers the coastline marks the distinction between land territories and maritime spaces. States have jurisdiction over their territorial seas, with a contiguous zone permitting enforcement, and a much more extensive Exclusive Economic Zone granting rights over natural resources. What might a terraqueous, posthuman map of the ocean look like? In the British Library, in London, a curious relic from Cook’s voyages in Oceania records Tupaia’s, Tahitian High Priest (arioi) and navigator for Cook in the eighteenth century, understanding of his world, later described as a ‘sea of islands’. For Tupaia a map integrates the perspective of the human and their relation to both land and sea. No god’s eye view so familiar in Western cartographies. Might a posthuman feminist encounter with maritime matters ask about this intertwined human, nonhuman, ocean, land, and dynamic understanding of the world?

Tupaia’s Map, 1770, British Library, London.

© British Library Board BL Add MS 21593.C

The ship

The container ships disrupted by Yemen attacks in February 2024 trace older colonial routes over the ocean. Port cities remember and record the attempts at ordering, the wealth arriving (and exported) from the colony to the metropole, the re-appropriation of land, property, people. Today ships inscribe a different sort of map of the ocean, that retraces colonial and imperial power, economic and extractive encounters, consumerism, and capital on a global scale.

The robot

Robot vessels are now deployed by militaries and shipping multinationals: named MASS – Maritime Autonomous Surface Ships - for commercial interests, and LOSV – Large Optionally-Crewed Surface Vehicles – for militaries. Coming soon to a military near you. Here the posthuman feminist takes pause. Might the human-nonhuman encounter be already drifting away from recognition of human-ocean, land-sea entanglements, as military-capital extend their technological tentacles and the autonomous, optionally-crewed vessels enact surveillance of the ocean. Here the map of the ocean is informed by older stories of deterrence through might, freedom of the High Seas, and the need for technology to know the ocean. Humans-out-of-loop might, in a near future, if not now, mean the battle between the ocean and the MASS.

And where is gender?

Returning to feminist analysis of women, peace and security, it is clear that military masculinities inform how we think about security. The intertwined map of military and capital produced by the ship and the robot reduces and refuses Tupaia’s understanding of the sea of islands, of humans living with and embedded in the nonhuman. Might a terraqueous feminism seek to know the ocean along with nonhuman kin, with indigenous and non-Western lore, and with a rejection of the violence that Enlightenment man – slavery, conquest, colonial expansion, extractivism, environmental harms – has already enacted? Here feminists would speak of the much longer military blockade of the ports of Gaza, using maritime might to starve and oppress, of the genocide on land that is replaced by a fear of commercial disruptions and deviations, where military-capital informs both human and nonhuman, land and sea encounters that reproduce the gendered and racialised Othering in the dominant cartographies of the world.

Gina Heathcote is a Professor of Public International Law at Newcastle Law School, Newcastle University, UK.

This article is original content published under a Creative Commons license CC BY-NC-ND 4.0